I Make Small Music A Minor Art So I Borrowã¢ââ ââ“ Serge Gainsbourg

| Serge Gainsbourg | |

|---|---|

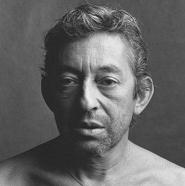

Gainsbourg in 1981 | |

| Built-in | Lucien Ginsburg (1928-04-02)2 April 1928 Paris, France |

| Died | 2 March 1991(1991-03-02) (anile 62) Paris, France |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1957–1991 |

| Spouse(s) | Elisabeth "Lize" Levitsky (k. ; div. 1957) Béatrice Pancrazzi (m. ; div. ) |

| Partner(s) |

|

| Children | 4, including Charlotte |

| Musical career | |

| Genres |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Labels |

|

| Associated acts | Brigitte Bardot Jane Birkin Charlotte Gainsbourg France Gall Alain Goraguer Jean-Claude Vannier |

| Website | Official website from Universalmusic |

Serge Gainsbourg (French: [sɛʁʒ ɡɛ̃zbuʁ] ( ![]() listen ); born Lucien Ginsburg;[a] ii April 1928 – two March 1991) was a French musician, singer-songwriter, actor, writer and filmmaker. Regarded as one of the nearly important figures in French popular, he was renowned for often provocative and scandalous releases which caused uproar in French republic, dividing its public opinion,[2] as well as his diverse artistic output, which ranged from his early work in jazz, chanson, and yé-yé to later on efforts in rock, zouk, funk, reggae, and electronica.[3] Gainsbourg's varied musical mode and individuality brand him difficult to categorize, although his legacy has been firmly established and he is often regarded every bit one of the world'southward well-nigh influential popular musicians.

listen ); born Lucien Ginsburg;[a] ii April 1928 – two March 1991) was a French musician, singer-songwriter, actor, writer and filmmaker. Regarded as one of the nearly important figures in French popular, he was renowned for often provocative and scandalous releases which caused uproar in French republic, dividing its public opinion,[2] as well as his diverse artistic output, which ranged from his early work in jazz, chanson, and yé-yé to later on efforts in rock, zouk, funk, reggae, and electronica.[3] Gainsbourg's varied musical mode and individuality brand him difficult to categorize, although his legacy has been firmly established and he is often regarded every bit one of the world'southward well-nigh influential popular musicians.

His lyrical works incorporated wordplay, with humorous, bizarre, provocative, sexual, satirical or destructive overtones. Gainsbourg wrote over 550 songs,[4] [5] which have been covered more 1,000 times past a range of artists.[6] Since his death from a 2d heart assail in 1991, Gainsbourg's music has reached legendary stature in France, and he has become ane of the land's best-loved public figures.[seven] He has also gained a cult following all over the world with nautical chart success in the Great britain and Belgium with "Je t'aime... moi non plus" and "Bonnie and Clyde", respectively.

Biography [edit]

1928–1956: Early years [edit]

Lucien Ginsburg was born in Paris on 2 April 1928. He was the son of Ukrainian-Jewish migrants, Joseph Ginsburg (27 March 1896, in Feodosia, Russian Empire — 22 April 1971, in Paris) and Olga[b] (née Besman; xv January 1894, in Odessa, Russian Empire (now Ukraine) – 16 March 1985, in Paris), who fled to Paris via Istanbul subsequently the 1917 Russian Revolution.[viii] Joseph Ginsburg was a classically trained musician whose profession was playing the pianoforte in cabarets and casinos; he taught his children—Gainsbourg and his twin sister Liliane—to play the piano.[4] Gainsbourg's childhood was profoundly affected by the occupation of France by Germany during World State of war 2. The identifying yellow star that Jews were required to wear haunted Gainsbourg; in later years he was able to transmute this retention into creative inspiration.[viii] During the occupation, the Jewish Ginsburg family was able to brand their way from Paris to Limoges, traveling under faux papers. Limoges was in the Zone libre under the administration of the collaborationist Vichy government and still a perilous refuge for Jews.[4] He attended the Lycée Condorcet high schoolhouse in Paris but dropped out before completing his Baccalauréat.[9]

In 1945, Gainsbourg's (Ginsburg's) father enrolled him into Beaux-Arts de Paris, a prestigious art school,[9] before switching to the Académie de Montmartre, where his professors included the likes of André Lhote and Fernand Léger.[10] [11] At that place, Gainsbourg would run across his first wife Elisabeth "Lize" Levitsky, daughter of Russian aristocrats who was besides a part-fourth dimension model.[9] They married on 3 November 1951 and were divorced by 1957.[9] In 1948, he was conscripted by the military for twelve months of service in Courbevoie. He never saw action and spent the fourth dimension playing dirty songs on his guitar, visiting prostitutes and drinking, subsequently admitting that the service made him an alcoholic.[9] Gainsbourg obtained work didactics music and drawing in a schoolhouse outside of Paris, in Le Mesnil-le-Roi. The school was set up under the auspices of local rabbis, for the orphaned children of murdered deportees. Hither, Gainsbourg heard the accounts of Nazi persecution and genocide, stories that resonated for Gainsbourg far into the hereafter.[8]

1957–1963: Early work as a pianist and chanson singer [edit]

Gainsbourg was disillusioned equally a painter equally he lacked talent but earned his living working odd jobs and as a piano actor in bars, usually equally a stand up-in for his father.[9] He soon became the venue pianist at the drag cabaret club Madame Arthur.[12] Whilst filling in a form to join the songwriting society SACEM, Gainsbourg decided to change his first name to Serge, feeling that this was representative of his Jewish background and because, as his future partner Jane Birkin relates: "Lucien reminded him of a hairdresser's assistant".[4] He chose Gainsbourg as his last name, in homage to the English painter Thomas Gainsborough, whom he admired.[13] Gainsbourg had a revelation when he saw Boris Vian at the Milord 50'Arsouille club whose provocative and humorous songs would influence his own compositions.[14] At the Milord fifty'Arsouille, Gainsbourg accompanied vocalist and club star Michèle Arnaud on the guitar.[x] In 1957, Arnaud and the social club'southward director Francis Claude discovered, with amazement, the compositions of Gainsbourg while visiting his house to see his paintings. The next twenty-four hours, Claude pushed Gainsbourg on stage. Despite suffering from stage fearfulness, he performed his own repertoire, including "Le Poinçonneur des Lilas",[15] [16] which describes the day in the life of a Paris Métro ticket human being, whose job is to postage stamp holes in passengers' tickets. Gainsbourg describes this task every bit and so monotonous, that the human eventually thinks of putting a pigsty into his own head and being buried in another.[17] He was given his ain show by Claude and was somewhen spotted by Jacques Canetti, who helped propel his career with a spot at the Théâtre des Trois Baudets and on his tours.[18] In 1958, Arnaud began recording several interpretations of Gainsbourg's songs.

His debut album, Du chant à la une !... (1958), was recorded in the summertime of 1958, backed by arranger Alain Goraguer and his orchestra, beginning a fruitful collaboration. It was released in September, condign a commercial and disquisitional failure, despite winning the one thousand prize at 50'Academie Charles Cross and the praise of Boris Vian, who compared him to Cole Porter.[xix] His next album, N° two (1959), suffered a similar fate. He fabricated his moving-picture show debut in 1959 with a supporting role in the French-Italian co-production Come Dance with Me, starring his time to come lover Brigitte Bardot.[xx] In the post-obit year, he featured as a Roman officer in the Italian sword-and-sandals epic-film The Revolt of the Slaves.[21] He would go on playing "nasty characters" in similar productions, including Samson (1961) and The Fury of Hercules (1962).[22] Gainsbourg's offset commercial success came in 1960 with his single "L'Eau à la bouche", the championship song from the film of the same name, for which he had equanimous the score.[23] L'Étonnant Serge Gainsbourg (1961), his third LP, included what would get one his best known songs from this catamenia, "La Chanson de Prévert", which lifted lyrics from the Jacques Prévert poem "Les feuilles mortes".[24] After a night of drinking champagne and dancing with vocaliser Juliette Gréco, Gainsbourg went home and wrote "La Javanaise" for her.[25] They would both release versions of the song in 1962, simply information technology is Gainsbourg's rendition that has endured.[24] His fourth album, Serge Gainsbourg N° 4 was released in 1962, incorporating Latin and rock and coil influences whilst his next, Gainsbourg Confidentiel (1963), featured a more minimalistic jazz arroyo, accompanied only past a double bass and electric guitar.[26] [27]

1963–1966: Eurovision and involvement in the yé-yé movement [edit]

Gainsbourg, Gall, and del Monaco at the Eurovision Song Contest, xx March 1965

Despite initially mocking yé-yé, a mode of French popular typically sung by young female singers, Gainsbourg would soon go one of its most of import figures later on writing a string of hits for artists like Brigitte Bardot, Petula Clark and France Gall.[13] He had met Gall afterward being introduced by a friend as they were Philips Records labelmates,[28] thus beginning a successful collaboration that would produce hits like "Due north'écoute pas les idoles", the frequently covered "Laisse tomber les filles" and "Poupée de cire, poupée de son", the latter of which was the Luxembourgish winning entry at the Eurovision Song Competition 1965.[29] Inspired by the 4th movement (Prestissimo in F minor) from Beethoven's Piano Sonata No. 1, the song featured double entendres and wordplay, a staple of Gainsbourg'south lyrics.[30] The controversially risqué "Les sucettes" ("Lollipops"), featured references to oral sex, unbeknownst to the xviii-year-old Gall, who thought the song was about lollipops.[29] Gall later expressed displeasure at Gainsbourg's antics, stating she felt "betrayed by the adults around me" in 2001.[31] Gainsbourg married a second time on seven January 1964, to Françoise-Antoinette "Béatrice" Pancrazzi, with whom he had ii children: a daughter named Natacha (b. eight Baronial 1964) and a son, Paul (born in bound 1968).[32] He divorced Béatrice in February 1966.[32]

His next album, Gainsbourg Percussions (1964), was inspired by the rhythms and melodies of African musicians Miriam Makeba and Babatunde Olatunji.[33] Olatunji later sued Gainsbourg for lifting three tracks from his 1960 album Drums of Passion.[34] Nevertheless, the album has been hailed as existence ahead of its time for its incorporation of world music and lyrical content depicting interracial dearest.[33] Betwixt 1965 and 1966, Gainsbourg composed the music and sung the words of science fiction author André Ruellan for several songs made for a series of animated Marie-Mathematics shorts created past Jean-Claude Forest.[35] He would reunite with Michèle Arnaud for the duet "Les Papillons Noirs" from her 1966 comeback record.[36]

1967–1970: Famous muses and duets [edit]

Bardot (left) pictured in 1968 and Birkin pictured in 1970

In 1967, Gainsbourg wrote the script and provided the soundtrack for the musical one-act television film Anna starring Anna Karina in the titular role.[37] [36] Another Gainsbourg song, "Boum-Badaboum" by Minouche Barelli, was entered by Monaco in the Eurovision Vocal Contest 1967, coming in fifth identify.[36] In that year, Gainsbourg would take a cursory but ardent love affair with Brigitte Bardot. One day she asked him to write the well-nigh beautiful love song he could imagine and, that night, he wrote the duets "Je t'aime... moi non plus" and "Bonnie and Clyde" for her.[38] The erotic yet contemptuous "Je t'aime", describing the hopelessness of physical love, was recorded past the pair in a small drinking glass berth in Paris. Just subsequently Bardot's husband, High german businessman Gunter Sachs, became aware of the recording he demanded it be withdrawn. Bardot pleaded with Gainsbourg not to release it and he complied.[2]

Bardot's LP Brigitte Bardot Testify 67 contained four songs penned by Gainsbourg, including duets such as the playful "Comic Strip" and the string-laden "Bonnie and Clyde", which tells the story of the American criminal couple and was based on a poem written by Bonnie Parker herself.[i] His own Initials B.B. (1968) included these duets and was his starting time album in nearly four years. Information technology blended orchestral popular with the style of rock feature of London in the swinging sixties, where the album was largely recorded.[39] Gainsbourg borrowed heavily from Antonín Dvořák'south New World Symphony for the title track, named afterward and dedicated to Bardot.[24] Phillips subsidiary Fontana Records as well issued the compilation LP Bonnie and Clyde (1968) comprising their duets and other previously recorded fabric.[forty]

His percussion heavy 1968 unmarried "Requiem cascade un con" was performed onscreen by Gainsbourg in the crime film Le Pacha, for which he was the composer.[41] Shortly subsequently being left by Bardot, Gainsbourg was asked past Françoise Hardy to write a French version of the song "It Hurts to Say Goodbye". The result was "Annotate te dire bye", which is notable for its uncommon rhymes and has become one of Hardy's signature songs.

In mid-1968 Gainsbourg fell in love with the younger English vocaliser and actress Jane Birkin, whom he met during the shooting of the film Slogan (1969).[4] In the film, Gainsbourg starred as a commercial manager who has an matter on his pregnant wife with a younger woman, played by Birkin.[43] Gainsbourg also provided the soundtrack and dueted with Birkin on the championship theme "La Chanson de Slogan". The relationship would terminal for over a decade.[44] In July 1971 they had a daughter, Charlotte, who would become an actress and vocalizer.[45] Although many sources country that they were married,[46] co-ordinate to Charlotte this was not the case.[44] After filming Slogan, Gainsbourg asked Birkin to re-record "Je t'aime..." with him.[2] Her vocals were an octave higher than Bardot's, contained suggestive heavy animate and culminated in imitation orgasm sounds. Released in February 1969, the song topped the Britain Singles Nautical chart after being temporarily banned due to its overtly sexual content. Information technology was banned from the radio in several other countries, including Spain, Sweden, Italy and French republic earlier 11pm.[47] The song was fifty-fifty publicly denounced past The Vatican.[48] It was included on the joint anthology Jane Birkin/Serge Gainsbourg, which as well contained "Élisa" and new recordings of songs written by other artists including "Les sucettes", "L'anamour" and "Sous le soleil exactement". In 2017, Pitchfork named information technology the 44th all-time album of the 1960s.[39] He and Birkin would share the screen in another Gainsbourg-scored picture, Cannabis (1970), in which he played an American gangster who falls in love with a girl from a wealthy family.[49]

1971–1977: Concept albums [edit]

Following the success of "Je t'aime... moi non plus", his tape company had expected Gainsbourg to produce another hitting. But subsequently having already fabricated a fortune, he was uninterested, deciding to "movement onto something serious".[50] The result was his 1971 concept album Histoire de Melody Nelson, which the tells story of an illicit relationship between the narrator and the teenage Melody Nelson after running her over in his Rolls Royce Silver Ghost.[51] The album heavily features Gainsbourg's distinctive half-spoken, one-half-sung vocal delivery, loose drums, guitar, and bass evoking funk music, and lush cord and choral arrangements past Jean-Claude Vannier.[51] Despite only selling around 15,000 copies upon release, it has go highly influential and is often considered his magnum opus.[51] An accompanying television receiver special starring Gainsbourg and Birkin was too broadcast.[52]

He suffered a center attack in May 1973, but refused to cut back on his smoking and drinking.[47] Gainsbourg's next tape Vu de l'extérieur (1973) was not strictly a concept album like its predecessor and follow-ups, despite its focus on scatology throughout. It largely failed to connect with critics and listeners.[50] [53] In that year, Gainsbourg also wrote all of the tracks on Birkin's debut solo album Di doo dah and he would continue to write for her until his death.[54] In 1975, Gainsbourg released the darkly comic album Rock Around the Bunker, performed in an upbeat 1950s rock and whorl style and written on the subject of Nazi Frg and the 2nd Earth War, cartoon from his experiences as a Jewish child in occupied French republic.[55] The adjacent twelvemonth saw the release of however some other concept album, Fifty'Homme à tête de chou (The Cabbage Caput Homo), a nickname used by Gainsbourg himself in reference to his large ears.[56] It included his offset foray into the Jamaican genre reggae, a style that Gainsbourg would record his next two albums in.[57]

In 1976, Gainsbourg also fabricated his directorial debut with Je t'aime moi not plus, an offbeat drama named subsequently his song of the aforementioned name. It starred Birkin in the lead function, with American actor Joe Dallesandro playing the gay man she falls in love with.[58] The film received positive critical notices from the French press and acclaimed managing director François Truffaut.[58] Having previously turned down the offering to score the popular softcore pornography film Emmanuelle (1974), he agreed to do so for ane of its sequels Farewell Emmanuelle in 1977.[59]

1978–1981: Reggae period [edit]

In 1978, Gainsbourg dropped plans to record another concept album and contacted several Jamaican musicians including rhythm section players Sly and Robbie with the intention of recording a reggae album.[sixty] He set off for Kingston, Jamaica in September to brainstorm recording Aux armes et cætera (1979) with the likes of Sly and Robbie and the female person backing singers The I-Threes of Bob Marley and the Wailers;[57] thus making him the first white musician to tape such an album in Jamaica.[61] The album was immensely popular, achieving platinum status for selling over one million copies. Simply it was not without controversy, equally the title track—a reggae version of the French national canticle "La Marseillaise"—received harsh criticism in the paper Le Figaro from Michel Droit, who condenmed the song and opined that information technology may cause a ascent in anti-semitism.[62] Gainsbourg also received death threats from right-fly veteran soldiers of the Algerian War of Independence, who were opposed to their national anthem beingness bundled in reggae way.[63] In 1979, a show had to be cancelled, considering an angry mob of French Army parachutists came to demonstrate in the audience. Alone onstage, Gainsbourg raised his fist and answered: "The true meaning of our national canticle is revolutionary" and sang information technology a capella with the audience.[64]

Birkin left Gainsbourg in 1980, but the 2 remained close, with Gainsbourg becoming the godfather of Birkin and Jacques Doillon'due south daughter Lou and writing her next 3 albums.[65] His outset alive album Enregistrement public au Théâtre Le Palace (1980), exhibited his reggae-influenced manner at the time. Also in 1980, Gainsbourg dueted with extra Catherine Deneuve on the hit vocal "Dieu fumeur de havanes" from the movie Je vous aime and published a novella entitled Evguénie Sokolov, the tale of an avant-garde painter who exploits his flatulence past creating a mode known as "gasograms".[66] His final reggae recording, Mauvaises nouvelles des étoiles (1981), was recorded at Compass Point Studios in The Bahamas with the same personnel as its predecessor.[67] Bob Marley, married man to The I Threes singer Rita Marley was reportedly furious when he discovered that Gainsbourg had made his wife Rita sing erotic lyrics.[63] New posthumous dub mixes of Aux armes et cætera and Mauvaises Nouvelles des Étoiles were released in 2003.[68] During this period, Gainsbourg also had success writing material for other artists, mostly notably "Manureva" for Alain Chamfort, a tribute to French crewman Alain Colas and the titular trimaran he disappeared at sea with.[69]

1982–1991: Final years and expiry [edit]

In 1982, Gainsbourg contributed his songwriting to French rockstar Alain Bashung's album Play blessures, which was a left turn creatively for Bashung and is often considered a cult classic despite negative contemporary reviews.[70] His second picture show as a director, Équateur (1983), was adapted from the 1933 novel Tropic Moon by Belgian writer Georges Simenon and is fix in colonialist French Equatorial Africa.[71]

Love on the Beat out (1984) saw Gainsbourg move on from reggae and onto a more than electronic, new wave inspired sound.[72] The album is known for addressing taboo sexual subject field matters, with Gainsbourg dressed in drag on the encompass and the highly controversial duet with his daughter Charlotte, "Lemon Incest", which seemed to ambiguously refer to the impossible physical beloved between an adult and his child.[72] [47] The music video for the vocal featured a one-half-naked Gainsbourg lying on a bed with Charlotte, leading to further controversy.[47] Yet, it was Gainsbourg's highest-charting song in France. In March 1984, he illegaly burned 3-quarters of a 500-French-franc bill on television to protestation confronting taxes rise upward to 74% of income.[four] In April 1986, on Michel Drucker's live Sabbatum evening television evidence Champs-Élysées, with the American vocalizer Whitney Houston, he objected to Drucker'south translating his comments to Houston and, in English, stated: "I said, I want to fuck her"—Drucker, utterly embarrassed, insisted that this meant "He says y'all are great..."[63] That same twelvemonth, in another talk evidence interview, he appeared aslope Les Rita Mitsouko singer Catherine Ringer. Gainsbourg spat out at her, "Y'all're nothing only a filthy whore" to which Ringer replied, "await at you, you're just a bitter erstwhile alcoholic...y'all've become a disgusting old parasite."[73]

Gainsbourg'south final partner until his decease was the model Caroline Paulus, amend known by her stage proper noun Bambou.[32] They had a son, Lucien (b. 5 Jan 1986), who now goes by the name Lulu and is a musician.[32] [74] His 1986 pic Charlotte for Ever farther expanded on the themes plant in "Lemon Incest". He starred in the film alongside Charlotte every bit a widowed, alcoholic father living with his daughter.[47] An album of the same name by Charlotte was also written by Gainsbourg.[75]

Tributes left at his gravesite

His sixteenth and final studio album, You're Under Arrest (1987), largely retained the funky new wave sound of Beloved on the Shell, but too introduced hip hop elements.[76] A return to concept albums for Gainsbourg, it tells the story of an unnamed narrator and his drug-addicted girlfriend in New York Metropolis. The album's anti-drug bulletin was exemplified by the single "Aux enfants de la chance".

In December 1988, while a judge at a film festival in Val d'Isère, he was extremely intoxicated at a local theatre where he was to do a presentation. While on phase he began to tell an obscene story most Brigitte Bardot and a champagne bottle, only to stagger offstage and plummet in a nearby seat.[73] Subsequent years saw his health deteriorate, undergoing liver surgery in April 1989.[77] In his ill health, he retired to a private flat in Vézelay in July 1990, where he would spend six months.[78] He connected to write for other artists, including the lyrics to "White and Black Blues" by Joëlle Ursull, the French entry in the Eurovision Song Competition 1990, coming in second place.[61] He similarly wrote all of the lyrics for popular singer Vanessa Paradis's anthology Variations sur le même t'aime (1990), declaring "Paradis is hell" after its release.[79] His last motion picture, Stan the Flasher, starred Claude Berri as an English teacher who engages in exhibitionism.[80] Gainsbourg'south last album of original material was Birkin's Amours des feintes in 1990.[81]

Gainsbourg, who was widely known every bit a heavy smoker, and smoked 5 packs of unfiltered Gitane cigarettes a day,[82] died from a heart set on at his home on 2 March 1991, a month shy of his 63rd birthday.[47] He was buried in the Jewish section of the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.[13] French President François Mitterrand paid tribute by saying, "He was our Baudelaire, our Apollinaire ... He elevated the song to the level of art."[2]

Legacy and influence [edit]

Tribute graffiti covers the outer wall of Serge Gainsbourg's house on the rue de Verneuil in Paris, looked after past Charlotte Gainsbourg after her father'due south death

Since his expiry, Gainsbourg'south music has reached legendary stature in France.[83] In his native state, artists like the bands Air, Stereolab and BB Brunes (who named themselves after Gainsbourg's song "Initials B.B."), singers Benjamin Biolay, Vincent Delerm, Thomas Fersen and Arthur H have cited him as an influence.[2] [84] He has also gained a following in the English-speaking world from artists like Jarvis Cocker of Lurid, Beck, Michael Stipe of R.E.K., Alex Turner of Arctic Monkeys, Portishead, Massive Attack, Mike Patton of Organized religion No More than and Neil Hannon of The Divine Comedy.[85] [51] [86] Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds guitarist Mick Harvey has recorded four comprehend albums sung in English.[87] Gainsbourg'south music has been sampled by several hip hop artists, including songs by Nas, Wu Tang Clan, Busta Rhymes and MC Solaar.[85] [88]

The Parisian house in which Gainsbourg lived from 1969 until 1991, at 5 bis Rue de Verneuil, remains a celebrated shrine, with his ashtrays and collections of diverse items, such equally police badges and bullets, intact. The outside of the house is covered in graffiti defended to Gainsbourg, as well as with photographs of meaning figures in his life, including Bardot and Birkin.[4] In 2008, Paris' Cité de la Musique held the Gainsbourg 2008 exhibition, curated by sound artist Frédéric Sanchez.[89] [90]

Comic artist Joann Sfar wrote and directed the biopic of his life Gainsbourg (Vie héroïque) (2010).[91] Gainsbourg is portrayed by Eric Elmosnino as an adult and Kacey Mottet Klein as a child. The moving picture won 3 César Awards, including Best Role player for Elmosnino, and was nominated for an additional eight.[92]

Discography [edit]

Studio albums

- Du chant à la une !... (1958)

- N° 2 (1959)

- 50'Étonnant Serge Gainsbourg (1961)

- Serge Gainsbourg N° iv (1962)

- Gainsbourg Confidentiel (1964)

- Gainsbourg Percussions (1964)

- Initials B.B. (1968)

- Jane Birkin/Serge Gainsbourg (1969)

- Histoire de Melody Nelson (1971)

- Vu de l'extérieur (1973)

- Rock Around the Bunker (1975)

- Fifty'Homme à tête de chou (1976)

- Aux armes et cætera (1979)

- Mauvaises nouvelles des étoiles (1981)

- Love on the Beat (1984)

- You're Nether Arrest (1987)

Notes and references [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ Ginsburg is sometimes spelled Ginzburg in the media, including print encyclopedias and dictionaries. Ginsburg is however the name engraved on Gainsbourg'south grave; Lucien Ginsburg is the name by which Gainsbourg is referred to, as a performer, in the Sacem catalog [ane] (along with Serge Gainsbourg as the author/composer/adaptor)

- ^ Short version: Olia, his mother's baptist proper noun was Olga, equally written on Gainsbourg'due south grave

References [edit]

- ^ a b Jones, Mikey IQ (ten September 2015). "A beginner's guide to Serge Gainsbourg". Fact. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ a b c d east Simmons, Sylvie (2 February 2001). "The eyes take information technology". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Torrance, Kelly Jane (13 Oct 2011). "An Unconventional Film for the Unconventional Serge Gainsbourg". Washington Examiner . Retrieved 1 Jan 2020.

- ^ a b c d east f g Robinson, Lisa (15 October 2007). "The Secret World of Serge Gainsbourg". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on viii March 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ fr:Liste des chansons de Serge Gainsbourg

- ^ fr:Reprises des chansons de Serge Gainsbourg

- ^ E.W. (12 October 2017). "In 'Rest', Charlotte Gainsbourg explores the sharp edges of grief". The Economist. Archived from the original on xiii January 2022. Retrieved xi March 2022.

- ^ a b c Ivry, Benjamin (26 Nov 2008). "The Homo With the Yellow Star: The Jewish Life of Serge Gainsbourg". The Forward. Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved iii May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Simmons, Sylvie (half-dozen June 2015). "Tolstoy's granddaughter. Dali's sleek couch. How Serge Gainsbourg became Serge Gainsbourg". Salon. Archived from the original on three Dec 2020. Retrieved 22 Jan 2021.

- ^ a b Giuliani, Morgane (ii March 2016). "Serge Gainsbourg : 9 lieux à visiter à Paris pour mieux connaître le chanteur". RTL. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 22 Jan 2021.

- ^ Searle, Adrian (25 November 2018). "Fernand Léger: New Times, New Pleasures review – humanity in a car age". The Guardian. Archived from the original on xviii Dec 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Discovering Serge Gainsbourg's Paris". Coggle. March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ a b c B. Greenish, David (2 March 2014). "This Day in Jewish History 1991: Controversial French Singer Serge Gainsbourg Dies". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Fifty'Arc Journal (#90) special issue devoted to Boris Vian, 1984

- ^ Rollet, Thierry (26 July 2018). Léo Ferré an artist'south life. p. 196.

- ^ Verlant, Gilles (15 November 2000). Gainsbourg. Albin Michel. pp. 132 to 134.

- ^ Grabar, Henry (12 April 2013). "Could Paris Terminate Upwardly With a Metro Station Named Later on Serge Gainsbourg?". Bloomberg CityLab. Retrieved 22 Jan 2021.

- ^ Kirkup, James (10 June 1997). "Obituary: Jacques Canetti". The Independent. Archived from the original on four May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ "Serge Gainsbourg". Encyclopedia.com. 29 May 2018. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved iv May 2021.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 31.

- ^ Morain, Jean-Baptiste (23 February 2021). "Gainsbourg et le cinéma : je t'aime, moi non plus…". Les Inrockuptibles. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved iii June 2021.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Dale, Paul (23 July 2010). "Five Neat Serge Gainsbourg flick soundtracks". The List. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c Allen, Jeremy (15 Jan 2014). "10 of the all-time: Serge Gainsbourg". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Guyard, Bertrand (24 September 2020). "Ne vous déplaise, Serge Gainsbourg a écrit La Javanaise pour Juliette Gréco". Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ "Serge Gainsbourg No. 4". AllMusic . Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Bromfield, Daniel (6 Jan 2019). "Serge Gainsbourg: Gainsbourg Confidentiel". Spectrum Civilization. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 42.

- ^ a b Genzlinger, Neil (viii January 2018). "France Gall, Adaptable French Singing Star, Is Dead at 70". New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 Apr 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Mahé, Patrick (xv January 2021). "Gainsbourg, le neat des mots". Paris Match. Archived from the original on vii March 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "French republic Gall & Serge Gainsbourg - The story behind "Les Sucettes"". 6 January 2010. Archived from the original on 30 Oct 2021. Retrieved three June 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b c d Marain, Alexandre (2 April 2021). "Serge Gainsbourg: the 8 women in his life". Vogue Paris. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved iii May 2021.

- ^ a b Tangari, Joe (11 August 2011). "Serge Gainsbourg Gainsbourg Percussions". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 2 April 2021. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Loret, Eric (xviii February 2011). "When Gainsbourg fooled effectually with Barbarella's sister". Libération. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved half dozen July 2021.

- ^ a b c Simmons 2001, p. 44.

- ^ Whitmore, Greg (fifteen December 2019). "Anna Karina, French new wave icon – a life in pictures". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Chocolate-brown, Helen (8 May 2017). "How Serge Gainsbourg'southward Je t'aime . . . moi non plus whipped up a scandal". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ a b Pitchfork Staff (22 August 2017). "The 200 Best Albums of the 1960s". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Neate, Wilson. "Bonnie and Clyde". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Banerji, Atreyi (8 February 2021). "Watch refurbished footage of Serge Gainsbourg in 'Le Pacha'". Far Out. Archived from the original on i March 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 50.

- ^ a b Adams, William Lee (26 January 2010). "French Chanteuse Charlotte Gainsbourg". Fourth dimension.com. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2010.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 68.

- ^ "All-time-Looking Couples E'er". Life.com. See Your World LLC.

Skillful, JoAnne (9 July 2011). "Inside Travel: Pooches in Paris". The Independent.

"Serge Gainsbourg'south women: the music". The Daily Telegraph. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

"Birkin, Bardot and Gainsbourg, the adventitious sex symbol". The Guardian. 5 July 2010.

"Jane Birkin". Apple Inc. - ^ a b c d e f Gorman, Francine (28 February 2011). "Serge Gainsbourg's 20 most scandalous moments". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ Spencer, Neil (22 May 2005). "The 10 nearly x-rated records". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ^ "CANNABIS (1970)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 27 Nov 2020. Retrieved 15 Feb 2022.

- ^ a b Simmons 2001, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Ewing, Tom (26 March 2009). "Histoire de Melody Nelson". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 8 Feb 2022. Retrieved fifteen February 2022.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 65.

- ^ Thompson, Dave. "Vu de L'exterieur Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Ruffner, Zoe (22 Jan 2021). "Jane Birkin on Her New Anthology and the Only Three Makeup Products She Uses at 74". Vogue. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 75.

- ^ Carroll, Jim (xvi June 2001). "Serge Gainsbourg". The Irish Times . Retrieved viii March 2022.

- ^ a b Simmons 2001, p. 87.

- ^ a b Kenny, Glenn (ten October 2019). "Je T'Aime Moi Not Plus' Review: Serge Gainsbourg'south Oddball Directorial Debut". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 Oct 2021. Retrieved viii March 2022.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 86.

- ^ a b Lynskey, Dorian (xv November 2021). "The House That Serge Built". Jewish Renaissance. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ "Serge Gainsbourg responds to an article past Michel Droit". Le Monde. 19 June 1979. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved ix March 2022.

- ^ a b c Chrisafis, Angelique (14 April 2006). "Gainsbourg, je t'aime". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 July 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Hird, Alison (3 March 2021). "Gainsbourg: notwithstanding France's favourite bad boy 3 decades on". RFI. Archived from the original on 23 Jan 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Egan, Barry (14 February 2021). "'People say plow over the page, but you don't want to, and then I wrote songs' - Jane Birkin on her daughter's expiry, Serge Gainsbourg and Je t'aime". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Mortaigne, Véronique (2019). Je T'aime The Legendary Love Story of Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg. Icon Books Limited. ISBN9781785785047 . Retrieved xi March 2022.

- ^ Pessis, Jacques (2 March 2021). "Le jour où... Gainsbourg est devenu Gainsbarre". Le Figaro. Archived from the original on 29 Jan 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Lavaine, Bertrand (27 June 2003). "Jamaican Gainsbourg". RFI. Archived from the original on nine March 2022. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ^ Minonzio, Pierre-Etienne (viii Nov 2020). "'Manureva', un tube qui vient de loin". France Inter. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved x March 2022.

- ^ Porte, Sébastien (4 July 2015). "Gaetan Roussel : 'Play blessures est l'album le plus risqué de Bashung'". Telerama. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved xi March 2022.

- ^ Siclier, Jacques (20 August 1983). "'ÉQUATEUR', de Serge Gainsbourg Les Blancs malades de l'Afrique noire". Le Monde. Archived from the original on xi March 2022. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b Anderson, Darran (24 October 2013). Serge Gainsbourg's Histoire de Melody Nelson. Bloomsbury Publishing Us. ISBN978-1-62356-597-8 . Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ a b Kent, Nick (fifteen April 2006). "What a drag". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Serge Gainsbourg Biography, Songs, & Albums". AllMusic . Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Hunter-Tilney, Ludovic (13 January 2012). "'I like being manipulated'". Financial Times. Archived from the original on ten June 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Simmons 2001, p. 115-116.

- ^ Los Angeles Times Staff & Wire Reports (6 March 1991). "S. Gainsbourg; French Singer and Composer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ Mathieu, Cloudless (two May 1991). "Gainsbourg, his last days of happiness". Paris Match. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved xiii March 2022.

- ^ Whitman, Chloe (13 September 2021). "Vanessa Paradis rétablit sa vérité sur sa relation avec Serge Gainsbourg". Gala. Archived from the original on nine March 2022. Retrieved xiv March 2022.

- ^ "'Stan the Flasher', la débandade d'une vie avec Claude Berri". Le Monde. 2 March 2011. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ "Unfinished sympathy: Jane Birkin on Serge Gainsbourg". BBC. 20 June 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Willsher, Kim (20 July 2016). "Smokers smoke as France mulls ban on 'too cool' Gitanes and Gauloises". The Guardian.

- ^ Nuc, Oliver (29 February 2016). "Gainsbourg est en railroad train de remplacer Trenet ou Brassens". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Sweeney, Philip (xvi April 2006). "Serge Gainsbourg: Filthy French". The Independent. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ a b Stephen Thomas, Erlewine (ii March 2016). "25 Mod Songs Inspired by Serge Gainsbourg". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on ix April 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Weiner, Jonah (3 May 2018). "Arctic Monkeys Start Over". Rolling Rock. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Allen, Jeremy (19 January 2017). "Jeremy Allen On Mick Harvey's Intoxicated Women". The Quietus . Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Grelard, Philippe (27 February 2021). "30 years later on, Serge Gainsbourg nevertheless a global influence". The Times of Israel. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Holman, Rachel (3 March 2013). "Twenty years on, Gainsbourg remains France's favourite 'enfant terrible'". French republic 24. Archived from the original on half-dozen March 2021. Retrieved 10 Nov 2015.

Frédéric Sanchez, who curated "Gainsbourg 2008" in Paris, describes him equally, "one of the almost important artists of the 20th century".

- ^ Litchfield, John (23 October 2011). "Je t'aime (over again): The French love affair with Serge Gainsbourg". The Contained. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 Nov 2015.

The curator of the exhibition, Frédéric Sanchez, describes the choice of Gainsbourg as a "consecration" and an "apotheosis".

- ^ Scott, A.O. (30 August 2011). "'Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life,' by Joann Sfar - Review". The New York Times' . Retrieved eleven April 2022.

- ^ Andersen, Nick (ii August 2011). "'Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life' Trailer Premieres". The Wall Street Journal . Retrieved 11 April 2022.

{{cite spider web}}: CS1 maint: url-condition (link)

Sources [edit]

- Simmons, Sylvie (2001). Serge Gainsbourg: A Fistful of Gitanes. London: Helter Skelter Publishing. ISBN1-900924-28-5.

- Clayson, Alan (1998). Serge Gainsbourg: View From The Exterior. London: Sancuary. ISBN978-1-86074-222-4.

External links [edit]

- (in French) Serge Gainsbourg official site

- Serge Gainsbourg at IMDb

- Serge Gainsbourg discography at Discogs

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serge_Gainsbourg

0 Response to "I Make Small Music A Minor Art So I Borrowã¢ââ ââ“ Serge Gainsbourg"

Post a Comment