Art Muic Amd Daance in South Africa During the 1800s

Roots in Africa

by Steven Lewis

Describing the African-American influence on American music in all of its celebrity and variety is an intimidating—if non impossible—chore. African-American influences are so fundamental to American music that in that location would be no American music without them. People of African descent were among the earliest non-indigenous settlers of what would become the Us, and the rich African musical heritage that they carried with them was part of the foundation of a new American musical culture that mixed African traditions with those of Europe and the Americas. Their work songs, dance tunes, and religious music—and the syncopated, swung, remixed, rocked, and rapped music of their descendants—would get thelingua franca of American music, eventually influencing Americans of all racial and indigenous backgrounds. The music of African Americans is one of the virtually poetic and inescapable examples of the importance of the African American experience to the cultural heritage of all Americans, regardless of race or origin.

Given its importance in American history and civilisation, exploring the history and affect of African American music is a key part of the mission of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. Music occupies a unique place in the museum both because of its importance in its own correct and the integral function that music and musicians played in all aspects of African American history, from civil rights struggles and religious ceremonies to social commentary and community edifice. Musical Crossroads, the permanent music exhibition at the NMAAHC, explores this history through the lens of five fundamental themes: Roots in Africa, Hybridization, Bureau and Identity, Mass Media & Entertainment, and Global Impact and Influence.

The most distinctive features of African-American musical traditions tin can be traced dorsum in some form or other to Africa. Many of the expressive performance practices seen every bit synonymous with African American music, including blue notes and call-and-response, have their roots in techniques originally adult in western and central Africa before arriving to the United States via the Eye Passage. Over the centuries, African American musicians have fatigued on the bequeathed connection to Africa every bit a source of pride and inspiration. Ane of the almost evocative illustrations of this connection from the NMAAHC drove is a wooden drum originally used in the Ocean Islands off the coast of Due south Carolina, probably in the 19th century. As an American manifestation of an African musical tradition, the drum illustrates one of many ways that African culture persisted in the United States, even during the long night of slavery.

Hybridization

Although the African elements of African American musical culture remain strong, the music of African Americans is a hybrid of the musical traditions of Africa, Europe, and Native American cultures, forth with other influences from around the world. This process, which began in the 17th century with the arrival of the offset enslaved Africans at Jamestown, continues into the present equally black musicians keep to draw on various influences to create new sounds. It is this hybridity that makes African American music a distinctly American miracle. A nineteenth century banjo in the NMAAHC'southward Slavery and Freedom exhibition is a vivid example of the fusion of African and European musical traditions that African Americans created in America.

The banjo was one of the most important instruments in early African American music, and though seldom associated with African Americans in contemporary popular culture, it is a classic example of the mode that African Americans composite African and European musical traditions together in the United States. The earliest banjos were likely based on West African lutes. Over the class of centuries, banjo makers gradually adapted their instruments to adapt to European tuning systems, resulting in a truly American instrument that incorporated Western music theory even as its design recalled its African models.

Jazz is another iconic example of African American musical hybridity that occupies a central position in the Musical Crossroads gallery. In the late 19th century, African American musicians combined popular songs and marches with African American folk forms like ragtime, sacred music, and the blues to create a new grade of heavily syncopated and improvisatory music. Jazz, as the music came to be called, today occupies such a cardinal place in America's cultural heritage that many fans and scholars call it "America's classical music." The Musical Crossroads gallery tells the stories of jazz musicians through their music and through objects such every bit a adapt jacket designed for jazz innovator and fashion icon Miles Davis.

Agency and Identity

Musical Crossroads uses objects to explore the means in which African American musicians and music lovers exercised personal agency and asserted their identities even in the face of daily humiliation and oppression by the American mainstream. Music played a central part in the African American ceremonious rights struggles of the 20th century, and objects linked direct to political activism bring to light the roles that music and musicians played in movements for equality and justice. A ticket to a 1963 concert of the Educatee Non-Violent Coordinating Commission(S.N.C.C.) Liberty Singers for case, immediately calls to mind the important role that music played in lifting the spirits of activists during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. The outfit associated with Marian Anderson's legendary 1939 performance at the Lincoln Memorial highlights another musical blow to entrenched racism. After the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her use of Washington, DC's Constitution Hall because of her race, Anderson gave a concert at the Lincoln Memorial to an audience of 75,000 people. The skirt and re-designed jacket from that concert evoke her celebrated operation.

Other objects in the Musical Crossroads gallery explore the artistic agency that many African American artists utilize to claiming stock-still notions of African American identity. There take always been blackness musicians who—in spite of overwhelming commercial force per unit area—insisted on remaining beyond category. The utterly unique singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist Prince was one of those fierce iconoclasts. From the start of his spectacular career, Prince struggled for commercial autonomy while defying racial, gender, and genre norms with his uncategorizable music.

Similarly, the Blackness Stone Coalition has spent decades debunking the stereotype of rock as "white" music by highlighting rock'due south origins in African American culture and showcasing gimmicky blackness stone musicians. This drum belonged to Will Calhoun, a fellow member of BRC-affiliated rock band Living Colour.

Mass Media & Entertainment

The appearance and evolution of the mass media and entertainment industries in the early 20th century was perhaps the single nearly important factor in the worldwide popularity of African-American musical forms that adult later the Civil State of war. The objects connecting mass media technologies to African American life and civilization stretch across nearly a century of history, encompassing a wide swath of American history and technological developments. Musical Crossroads presents items ranging from a phonograph owned by an early 20th century black family to the MIDI Production Middle and Minimoog synthesizer used by trailblazing hip hop producer J Dilla.

Other objects, like the Soul Train Artist of the Decade trophy awarded to Whitney Houston [Photo Soul Railroad train Award2014.161.five] or the microphone box used on early hip-hop TV evidence Video Music Box [Microphone Box 2015.188], point to television receiver'due south importance as a medium for African American music.

Global Bear upon and Influence

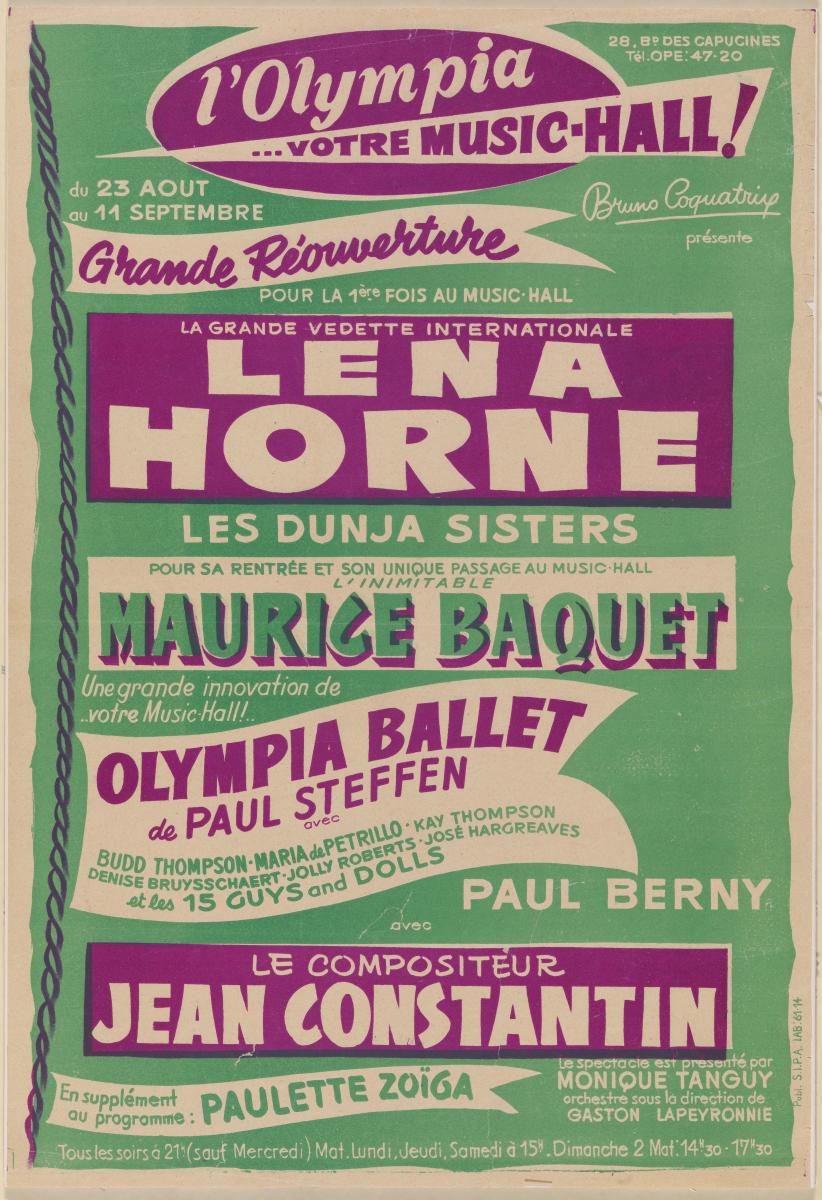

In addition to their fundamental influence on American culture, the stories about African American music being told in Musical Crossroads had a seismic affect on world musical culture. Considering of mass media technologies and the broad influence of American culture on music around the world, African Americans' musical innovations accept influenced artists in most every corner of the world, and at that place are enthusiastic international audiences for black musicians. Promotional materials from international tours by African American artists including Lena Horne and the Black Rock Coalition demonstrate the touch on that practitioners of African American music accept had on global pop culture.

Whatever story of the global impact and influence of African American music as well needs to include explorations of the Afro-diasporic connections that continue to enrich the music of the Americas and the globe. African American musicians throughout history have drawn inspiration from African-derived music in the Caribbean area and Latin America, besides as the African continent itself.

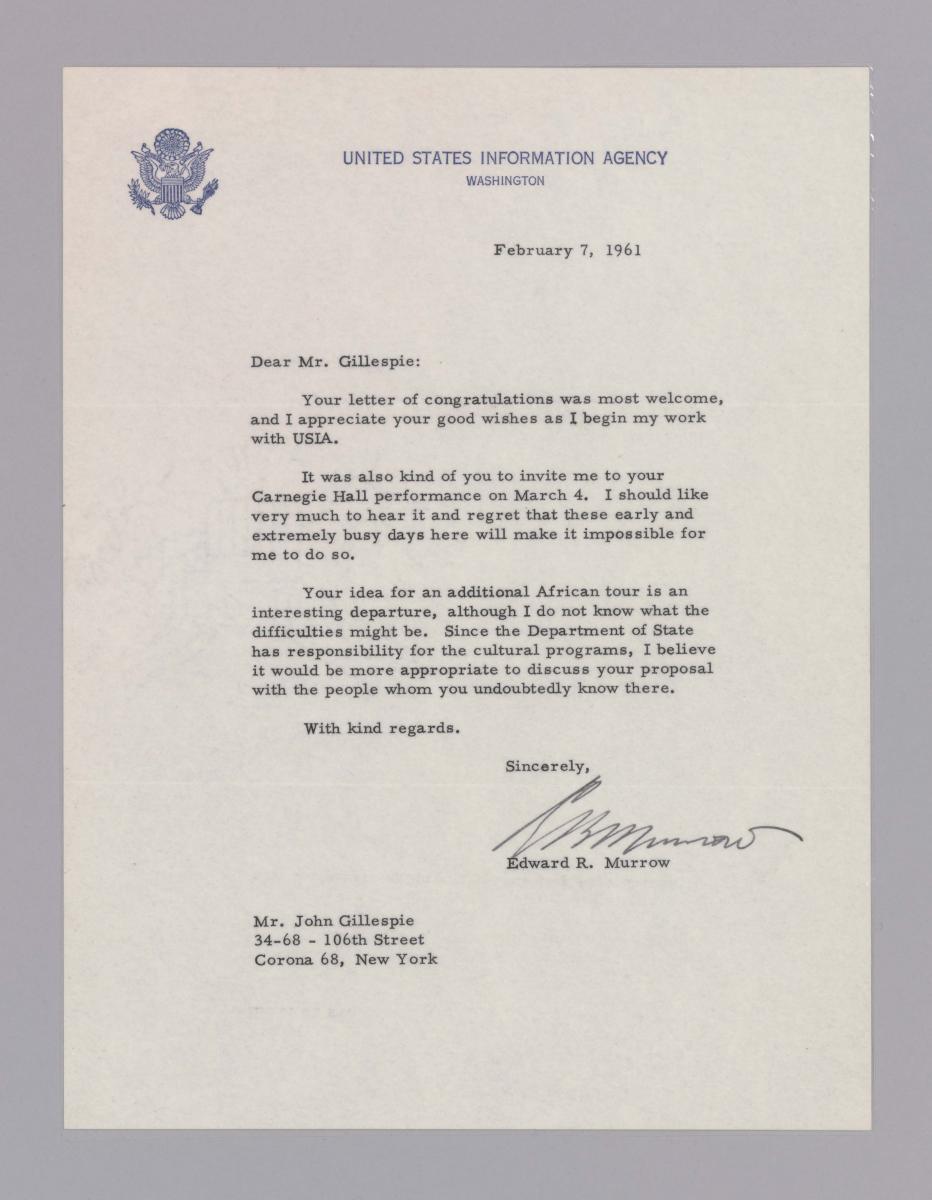

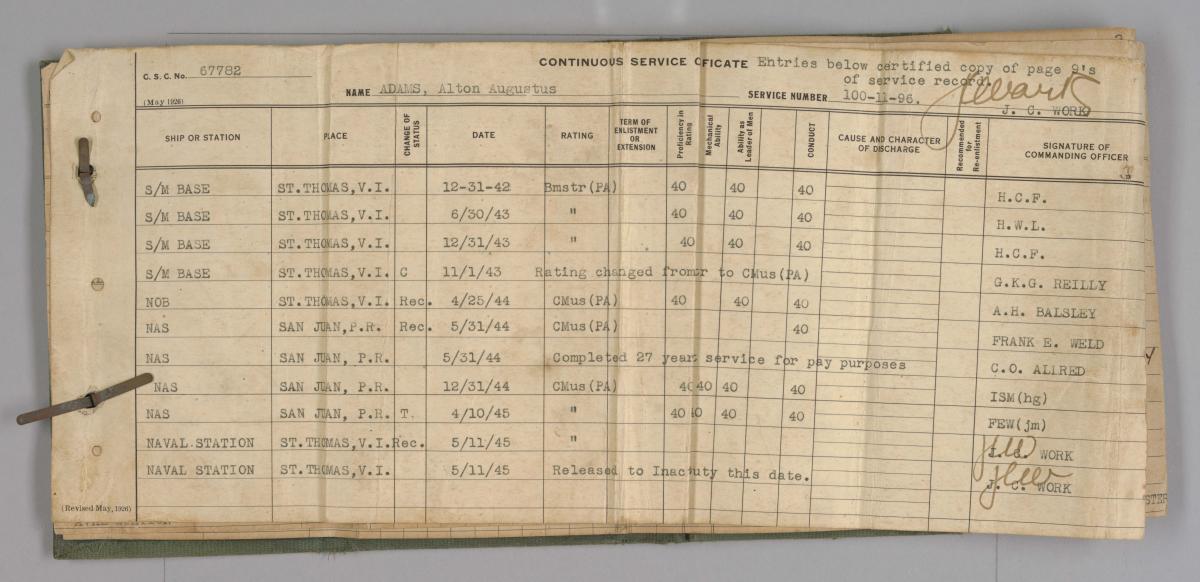

Trumpeter John Birks "Featherbrained" Gillespie'due south embrace of Afro-Cuban music, for case, was a crucial moment in the development of Latin jazz, and he maintained close ties with Latin American musicians and audiences throughout his long career. Countless black musicians from elsewhere in the diaspora have made their mark on American music history. Born in the Virgin Islands in 1889, composer and bandleader Alton Adams became the offset black bandmaster in the United States Navy in 1917.

Even more influential was Cuban-American salsa legend Celia Cruz, whose dress is featured in the Musical Crossroads gallery.

The Musical Crossroads gallery uses the NMAAHC'due south incredible array of artifacts to explore and gloat the rich African American musical legacy. Featured objects ranging over centuries of creativity, struggle, and triumph tell the stories of African American artists and communities whose songs rang out despite America's long history with systemic racism. Despite these circumstances, these musicians—famous, obscure, and unknown—continue to be the wellspring of America'southward musical heritage.

Source: https://music.si.edu/story/musical-crossroads

0 Response to "Art Muic Amd Daance in South Africa During the 1800s"

Post a Comment